Architecture Deep Dive: Why CtrlB’s LSM Approach Outperforms MergeTrees for Observability.

Feb 12, 2026

Introduction

ClickHouse is a remarkable piece of engineering. Its MergeTree engine has rightfully earned its place as the gold standard for OLAP, processing billions of rows to answer analytical questions like "What was the average revenue last quarter?" with incredible speed.

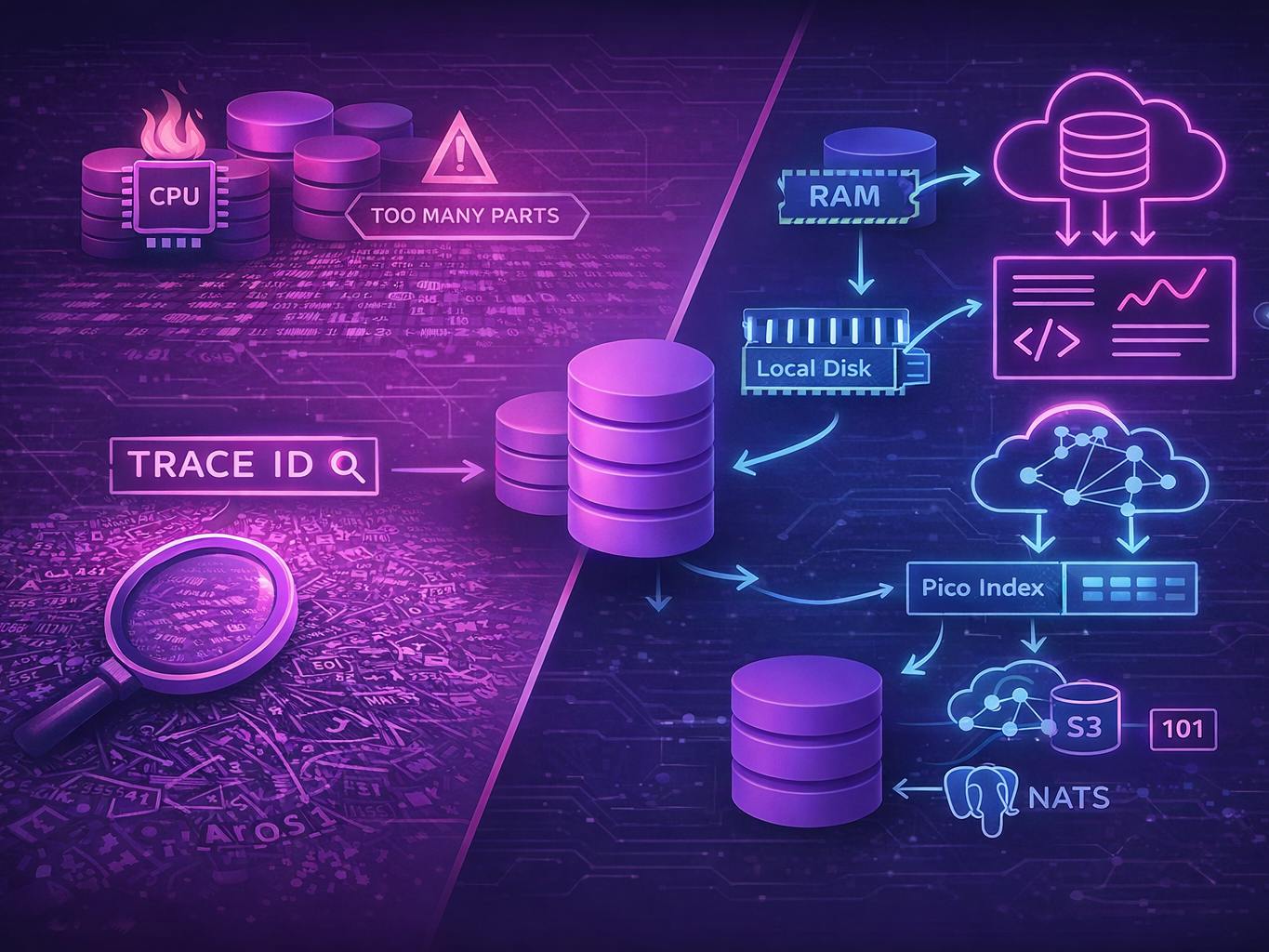

However, observability is a fundamentally different challenge. When an engineer is debugging an outage, they aren't looking for averages. They are hunting for a needle in a haystack—a specific Trace ID, a unique error log, or a single causal event—hidden within a chaotic, bursty stream of high-cardinality data.

While ClickHouse attempts to adapt to this workload using sparse indexes and rigid parts, we built CtrlB from the ground up using a decoupled Log-Structured Merge (LSM) architecture. By treating storage, indexing, and coordination as independent components, we solve the specific pain points that traditional analytical databases struggle with.

Below is a breakdown of why our architecture—powered by S3, Postgres and NATS—provides a more resilient solution for observability workloads.

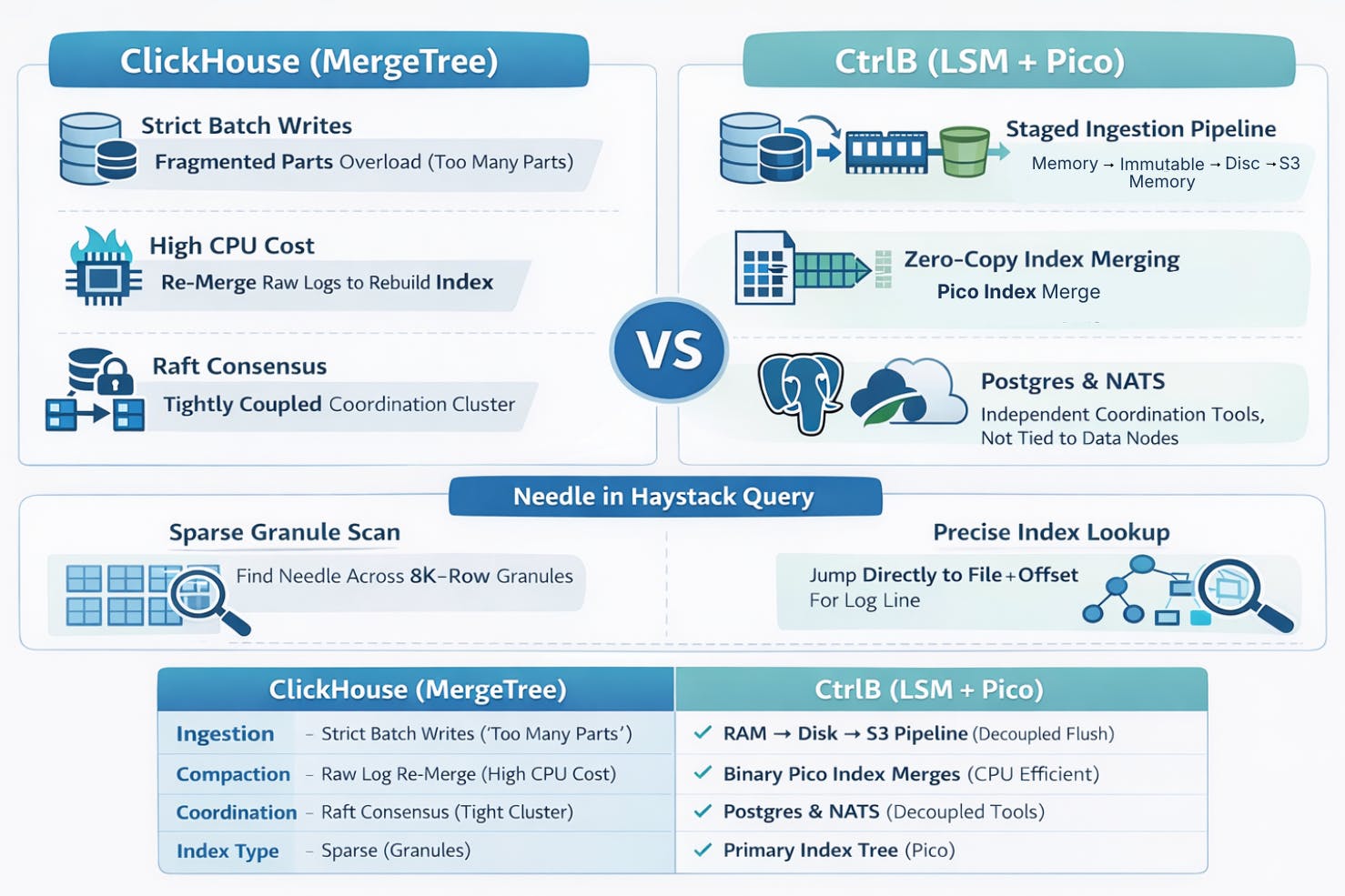

1. Solved: The "Too Many Parts" Ingestion Bottleneck

One of the most common frustration points for ClickHouse users is the dreaded DB::Exception: Too many parts error.

In the standard ClickHouse MergeTree model, data is written into directories called "parts" on the local disk. To maintain performance, the database requires writes to be heavily batched (e.g., 10,000 rows at a time). If an application streams real-time logs directly, it generates thousands of tiny parts. The background merger simply cannot keep up with this fragmentation, causing the database to lock up. This usually forces teams to manage complex external buffers, like Kafka, just to feed the database safely.

The CtrlB Approach: A Multi-Stage Flush

We decided to decouple ingestion completely using a tiered buffering strategy. This allows us to absorb massive traffic bursts without them ever impacting long-term storage stability.

The data flows through four distinct stages:

- Memory (Mutable): Incoming data lands in a mutable in-memory buffer (Memtable), allowing for instant acknowledgement.

- Immutable Memory: Once filled, this buffer freezes into an immutable state, while a new buffer is immediately created to handle fresh writes.

- Local Disk: The immutable block is flushed to the local disk to ensure durability.

- S3 Upload: Finally, these files are uploaded to Object Storage (S3) for permanent, cost-effective storage.

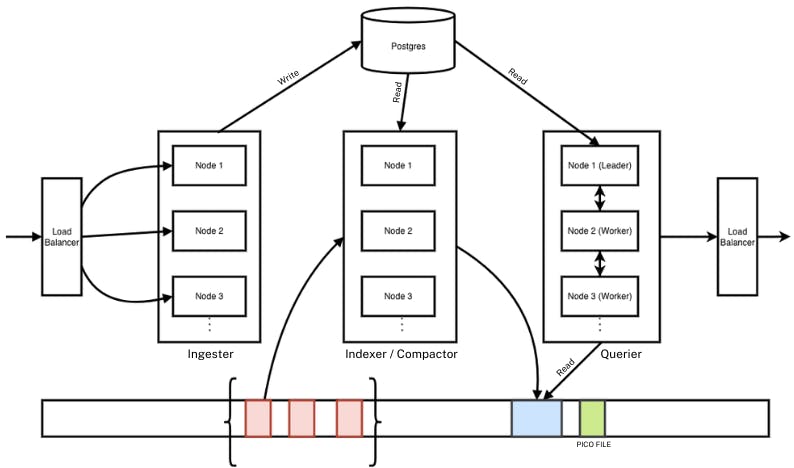

Crucially, we only update our metadata in Postgres (the file_list table) once the file is safely in S3. This architecture eliminates the "too many parts" failure mode.

2. The Pico file (solving the compaction task)

This is the most significant divergence between our architecture and traditional databases.

In a standard MergeTree, when background compaction triggers to merge several small files into a larger one, the database often has to re-read the raw data to rebuild the primary index. This is computationally expensive—essentially "work about work"—burning CPU and I/O re-processing logs that haven't changed.

Our Innovation: Binary Index Merging

CtrlB uses a dual-file format: the Data File (Parquet) and a separate Primary Index (which we call the Pico File).

When our Compactor merges small files, it doesn't touch the raw Parquet data. Instead, it reads the corresponding small Pico files. Because these index files are sorted binary sketches, the compactor can simply perform a binary merge on them directly.

Think of it as Index A + Index B = Index C.

By stitching these small indexes together without re-reading the heavy raw data, our compaction process becomes orders of magnitude lighter and faster. We avoid the heavy lifting that other systems perform when organizing old logs.

CtrlB's Architecture-

3. Decoupled co-ordination - Postgres & NATS

State management in distributed databases is notoriously difficult. Distributed coordination is the "hard part" of any database. Modern ClickHouse has moved to ClickHouse Keeper, a C++ implementation of the Raft consensus algorithm. While it removes the old Java dependencies, it still requires a tightly coupled consensus quorum. This means you must manage a "brain" of 3 or 5 nodes that must stay in perfect sync. If the Keeper nodes experience disk latency or network partitions, the entire cluster's ingestion and replication can freeze.

CtrlB takes a "Separation of Concerns" approach by using two industry-standard, independent tools:

We opted for a simpler, decoupled approach using industry-standard tools that live independently of the data nodes:

- Postgres as the Source of Truth: We use two tables, file_list and index_list, to track files in S3 and their indexing status. When a file arrives, it is marked as "unindexed." An asynchronous indexer simply asks Postgres "What needs work?", processes the file, and updates the status.

- NATS for Query Coordination: We don't rely on static shard maps. When a query arrives at a Leader node, it asks NATS "Who is available to work?". The work is then dispatched dynamically to available Worker nodes.

This separation allows us to scale our compute (Queriers) independently of our storage (S3) and our coordination logic.

4. The “Needle in Haystack” query

Finally, there is the query performance itself. ClickHouse uses a Sparse Primary Index that points to "Granules" (blocks of ~8192 rows). To find a specific log line, it often has to scan that entire block. This is excellent for range queries but mediocre for the unique point lookups common in observability (e.g., "Find this specific Trace ID").

Because CtrlB merges its Pico files into a clean tree structure, the root of our LSM tree can guide the query engine to the exact file and offset required. We don't scan unrelated data blocks; we traverse a lightweight index tree to jump straight to the data you need.

What’s Next

In the next part of this series, we’ll share a detailed benchmark and architectural comparison between ClickHouse and CtrlB. We’ll look at ingestion performance, compaction efficiency, query latency, and operational complexity under real-world observability workloads.

Our goal is to move beyond theory and show measurable differences in how each system behaves at scale.